Johnny Marr, part 1

This interview was conducted over the course of several sessions, May – July 2012. The interview will be published in 3 parts. Thank you, Johnny, for your time and for the depth of your answers.

PART 1: MANCHESTER / SCHOOL DAYS / FAMILY / TROUBLE / DRUGS

How are you?

I’m OK. I’m pretty good. I’m working really hard, as always. The record’s going all right. It’s a lot of work, but I like work. I kind of forgot that I’d be the producer and the singer and all that. That means I have to be there for everything, really. I’m not complaining. I’m spinning all these plates, but I still wake up in the morning really happy that I get to make music.

When you wake up is it usually morning?

Well, that’s a figure of speech… But I do. I wake up really really early. For the last five or six years I sleep in these little three or four hour bursts and then I get these creative ideas around three o’clock in the morning. Sometimes I go to bed late and then wake up two hours later and I’ve got a better song.

Are you happy with that or does it feel like a sleep disorder?

No, I’m happy with it because I’m sure I’ll get to do lots of sleeping when I get older — too much sleeping. I’m happy with it because I’m overrun with ideas. They might not all be good, but it’s nice to be flooded with ideas about things. I think that’s why I stay awake. I have sort of strange sleep patterns. Sometimes I’ll just go on these jags, go for walks around the city in the middle of the night.

You mean when you live-tweet your adventures? So these adventures actually happen?

It depends. The helicopter one was real.

How about when you were tweeting from a train station at night?

Oh, yeah — that was fantastic. I do that a lot. Manchester’s great for that kind of thing. I don’t know how it is in America, but in Manchester it’s not too scary out late at night. It’s kind of scary if there are lots of people coming out of bars, etc., but in the dead of night it’s all right.

When I was a teen I thought Manchester was the most exotic place on earth.

Well, it was for me as well… And I lived it.

Really? Why?

That’s one of the reasons why I’m here — I’ve got an affection for the city. I’m really proud of coming from Manchester. One of the reasons I’m here is because I think it’s the best city to be in. I still see things about it that were romantic when I was a kid. It’s still kind of romantic now, really.

It’s changed a lot though, hasn’t it? It used to seem more grey and sad to me. It no longer seems quite that way. Am I wrong?

No. That’s right. I have kind of mixed views about that. I’m glad for young people — that they’re not standing around in litter, and they’re able to get a tram and enjoy the advantages of the modern place, but it doesn’t look quite as poetic. The interesting thing is that in the late ‘70s, when I was in my early teens, there was a feeling around the city that the future was going to be a sort of dystopia, and part of dystopia was this poetic landscape… But the thing that happened was that we all got a lot more comfortable and the poetry got killed off by luxury.

Yet you’re still there.

Well, it’s the best place to make music and that’s why I came back from Portland. My family will support me and be excited and involved in whatever I’m involved in… And they’ll be wherever I am. There’s no separation between my work and my family. Just like there’s no separation between me and my son’s work. We’re all sort of in it together, really. We’re a pretty creative family. There’s no distinction between family life and work life.

What were you like as a child?

I was really sensitive and really quiet. My sister is 11 months younger than me, which is known as having an Irish twin. Me and my sister were very very close up until age 15, 16, 17 — which is quite unusual, I think. I grew up in an environment that was intense. It was intensely religious, intensely Irish, intensely musical, and intensely young.

My parents were very young when I was born. They were about 17 or 18. Growing up I had very tight relationships with several women who were very young as well. My memories of being, say, 5 and 6, are of spending a lot of time hanging out with 22 and 23 year old women. They were enjoying a sort of liberation after coming from little villages in Ireland. It was very working class and very Irish. There wasn’t a lot of money around, but it was a lot compared to where they’d left.

They were full of vibrant energy. They were from the country. They weren’t quite hell raisers because they were very Catholic, but if they weren’t Catholic they would’ve been raising hell. There were a lot of parties. There was a lot of struggle. I’m trying not to sound too melodramatic, but I really felt a lot of intensity and drama around me. There were a couple of streets where my relatives all lived. This big family of young Irish kids all moved to Ardwick Longsight. My mother comes from a family of 14 and my father comes from a family of 7. They came over en masse and I was one of the first kids, so I was often in charge of younger children.

When I was ten I got moved out to the suburbs from the inner city. I’d already started playing the guitar and because I’d come from the inner city I was already pretty into my clothes. My relationship with my sister was quite important. The two of us looked a lot alike. We arrived in this suburban town that had a reputation for being pretty tough, but the place we’d come from, Ardwick, was much much tougher, so it was like arriving in Beverly Hills for us.

The other thing about my childhood, I realize now, is that I was spoken to like I was an adult. Nothing was really off limits in terms of what the adults talked about. They weren’t too paranoid about what they would discuss in front of us in terms of who had been fighting with who and who hadn’t come home for two days and which uncle had been thrown out and which uncle was about to be thrown out and why. So there was a lot of very grown-up conversation around me all the time. The language was very colorful and the drinking was even more colorful… as was the dancing. In that order.

When the adults asked me about my guitar playing it was in a quite serious fashion. Things like “how long have you been playing”, etc. They all played — not professionally or anything like that — and it was assumed that you were going to be good. From a musical point of view I had these part-time musicians and full-time obsessives assuming that I was working towards being very good. It was never assumed that I was ever going to make money at it because that was for people on Mars. The mindset of my environment was that we were lowly. Because of the class system, and particularly when you’re from another country, it was unthinkable that you’re going to end up with a big house or anything like that.

You often speak of your mother, but you rarely mention your father. What’s he like?

He’s really quiet. When I got to about 10 or 11 he didn’t really know how to communicate with me. He’s not a great communicator anyway, and that’s all right. He’s a quiet guy. As I’ve gotten older, you know, …my dad’s a good guy. I like him.

Do you hang out with your parents and siblings much?

Not really. They let me sort of live this sort of artistic life and don’t trip on me too much. I really appreciate it because when you get into adult life a lot of people’s parents make them feel guilty for not calling. My parents don’t do that. We don’t even live that far away, but they just know I’m really busy. They’ve been pretty consistent with that. They let me do my own thing from the time I was 14 or 15. Younger, really, because I was going to concerts when I was about 11 or 12.

Do you ever see your extended family? Aunts, cousins, etc?

No, never. Never. I haven’t seen them since I was 14 or 15. When I started to imagine the reality of being able to get away from my environment I did everything I could to do that. It started out with getting into the City Center and hanging out there, seeing whatever shows were going on, hanging out in shops and bars and then hanging out in strangers’ houses because they were people I could write songs with. Mostly musicians. I was pretty fearless like that. I spent a lot of time at Andy Rourke’s house at the time. I slept at his house a lot. That was pretty wayward because his parents didn’t live there. They split up and his dad was away on business all the time. So we were like brothers. It was Andy and his three brothers and me and Angie. I spent a lot of time at Andy’s from the time I was 15, then, as soon as I knew how to sneak onto the train from Manchester without paying, I just extended my travels to London. That was very handy because Billy Duffy, who was older and a musician and had a little flat in London, was working in a clothes shop. Billy was kind of my go-to in London… whether he liked it or not. So he had this kind of little truant friend who would just kind of turn up on a Friday and crash at his house until Monday or Tuesday.

Yes. Well, we were supposed to be, but in the last couple years me and Andy didn’t really go to school very much. Then we were invited to continue our absence. We weren’t expelled because they just couldn’t be bothered bestowing that honor on us — “If you’re not going to bother coming we’re cool with that.” So the last year we really didn’t go to school.

When you became a parent were you more protective of your kids than your parents were with you? Does it shock you how unsupervised you were?

I was more protective, but I think we live in a tougher world now. My mother was very young and coping with two children without a lot of money. The fact that I was quiet and I was able to escape through pop music, that meant pop music was, in a way, like a babysitter for me. From the time I was about five I’d stand upon a chair and stay stood on the chair in front of the radio for 2 or 3 hours after school. My mother would clean the house and just leave me to it, completely uninterrupted. My family used to tell me stories about how obsessive I was about music, how I was unusually drawn to it. …A movie came out about twelve years ago called “East Is East” that’s set in the UK in the late ‘60s. There’s a lot of corny pop songs from the day as the soundtrack — songs I wouldn’t have heard since I was 5 or 6. While I was watching this movie I knew every word to the songs. If an oldies station is on and a record comes on that I’ve got no business knowing — some Drifters song that I don’t even know I like — I’ll know all the words inside out. So I know they’re not exaggerating.

When you do a lot of interviews over the years you start to wonder how much of what you’re remembering is mythology or whether you’re just trying to make yourself sound more interesting at times. So, a few years back I checked with my parents about this story I’ve told about how they’d leave me in a department store and take off. My mother said it’s true. I said to her “It’s weird — I must have just been drawn to the shape of the guitars.” She said it wasn’t just the guitars though; it was the amplifiers as well. I don’t know why that is… I always wanted to escape.

Escape from what?

I wanted to escape the world. I wanted to escape what I was around and what I was hearing… the conversations I was having with people… people’s personalities — life. I wanted to escape my consciousness, my feelings, what I was seeing. It’s like how Wordsworth wrote The World Is Too Much With Us. I had a love of music and a love of melody and rhythm and sounds and all the things that make up pop music. I needed it to escape normal life. I still do, but I really did then. It’s more of a need than just an attraction.

Did your parents support that or were you told to be more sensible?

The second thing you said. They loved that I was passionate about music because they’re passionate about music as well. They were proud of that, but I had to fight with them quite a lot as a teenager because I wanted to be a professional musician. It must have been hard for my dad because I was kind of wild in a way. I was nice, but in my teens I was kind of wild. I was so idealistic and very energetic.

When we moved to the suburbs I changed a lot. It was like starting over for me. Moving really set me free. It was amazing. No one knew the real me and because I played guitar everyone assumed that I was very confident, so I learned how to be confident. I just reflected what they thought I was. I suppose it was the other side of me.

That’s interesting because I’ve always felt like our personalities are mostly formed at birth, but it sounds like you did a lot of changing.

That original side of me that was there when I was born and when I was young is still there. That side’s never gone away. I just learned not to be timid.

Did you make an effort not to be timid?

No, I got lucky — this vivacious side just came out and I got kind of brave. It’s all because of the guitar. It gave me an identity. I didn’t know it was such a big deal until I moved to a new place. I was a new kid who came into a school… I came from the inner city… I had this guitar and I got quite a lot of attention, so I just rolled with it.

Is it true that you had some trouble with the law when you were a teenager?

Oh, [shy smile]…yeah.

And now you’re an upstanding citizen. What changed?

I was never a bad person. I was never not a nice person, I don’t think. I was just a little wild and very daring. I wasn’t scared of anything. But I always liked people and I was never violent. I would never do stuff like stealing from a person or anything like that. I liked a bit of devilment and a little bit of being dangerous and pushing the limits, but I have a good survival instinct as well. When I was younger I was always around people who were much crazier, but I was able to draw a line and not go too far with things… whether it was drugs or any kind of recklessness. I always wanted to experience a lot of things.

May I ask what you got in trouble for?

[Shy.] Oh… stealing.Were you ever arrested?

Yes. A couple of times.

Did that scare you?

It did the last time because it looked like it was really serious. The big trouble I got into was not because I stole something; it was because one of my friends stole some art. I had introduced him to this dodgy guy and I got caught in the middle of it… But that was just me being a nice guy. This guy was just bothering me so much. His friend had acquired some stolen art. He thought I would have some contacts in the underworld… which I kind of didn’t. [smiles] But I’m quite resourceful, so I found out who the local contact was in the underworld who specialized in these kinds of matters and put Mr. X with Mr. Y and all shit broke loose. It was really quite serious. It was kind of a learning curve. It sort of toughened me up. Years later I can say that I do have the honor of having been busted with my guitar plugged into my amp, so several million rock ‘n roll points to me. [smile]

Why did you legally change your name to “Johnny Marr?” Was your family upset about that at all?

I was so young when I decided to do it. It didn’t really occur to me at that age that it might hurt my parents’ feelings. I’m not sure whether it did, but when I got to be well known, at first, I think it was a bit awkward for them having to explain that I had a different name. It’s very simple — the first time I thought it would be cool to have a different name was when more people started to call me “Johnny.” My parents still call me “John.” It’s kind of endearing, really. It makes them different from everybody else.

Also, it was because I was so into Marc Bolan. He changed his name from M-A-R-K to M-A-R-C… And because my name could work with an M-A-R I think there was quite a bit of that in it as well. I used to write it on my books. It’s not that far from M-A-R-C to M-A-R-R. I think that was subconsciously in my mind. Then when The Buzzcocks came out and their drummer had the same name I knew I had to change it even though I was only maybe 14. I thought OK, this person’s in the same profession as me… even though it was a long way before I was professional. That shows you how determined I was to make my living as a musician. That was the main reason I changed it. I even told school that they had to change my name. There was one other thing as well — if you’re called “Maher” it’s only people in Ireland who can pronounce it. They know it’s pronounced mar. In England everyone says may-her… or mayer or mah-ther. I changed it legally as soon as I could afford it; I changed it when The Smiths started.

People who change their names are a certain kind of person, don’t you think?

Yes. People who are aware of their identity. A lot of people don’t care about their identity in that way. They’re not objective about it. Also, a lot of people would never dream of it because they think it’s a disloyalty to their family. None of that ever occurred to me. Everything was just about being a glam rock guitar player, and then later it was about being a new wave guitar player… and I’ve never shut that off.

So, if you drew your new name on your books, did you also draw guitars all over everything as well?

I did, yeah. I have to restrain myself from still doing that now. [smiles] I was really into, in this order — playing the guitar, records, clothes, girls, football, and pot. Sometimes it shuffled around a bit. Sometimes all at once.

When I talk about drugs — it wasn’t really too sordid. That was part and parcel of the culture I grew up in. Everybody in my neighborhood smoked pot and took pills like loads of musicians do. Particularly working-class British musicians, I think. It was just something to do for fun. I was never one of those teens standing around the street messed up. I did have some kind of sophistication about it. It was just regular teenage stuff.

It was the lifestyle I wanted; it wasn’t random. It all seemed to make sense. In that regard I’m really the same as I was then. I see a lot of value in what I pursued. Pretty much all of that has been useful for my life as an adult.

Yes, you seem too smart to let drugs stop you from doing what you wanted to do.

I’m also not that interested in it. I never really was. Doing something creative was always way way …way way more important. During the Smiths days — you don’t get to make that many records at that kind of speed and quality if you’re goofing off. …On anything. You just don’t. The work always comes first for me. It’s the same with my family. We all understand, as a group, that the work comes first. I was saved by loving work, my survival instinct, and just common sense… and also a kind of decorum — I’m not into getting messy. It’s good to have a certain amount of dignity even when you’re partying.

What changed you into a healthy sort? Did you just wake up one day and say “I’m not going to smoke or drink and I’m going to run 20 miles a day?”

Kind of, but it wasn’t just one morning. It was a gradual thing in the early 2000s. It started sometime earlier when I met some hip-hop guys who used to work for the band Naughty By Nature. I asked them why, in hip-hop videos, everyone was so buff and working out all the time. In the videos, while they were singing, people were almost doing press-ups. It was explained to me that it was the idea of progressive strength and wanting to be on top of your game. Particularly because amongst urban blacks at that time there were a whole bunch of guys walking around, with brown paper bags, sucking on a 40, and then there was a reaction against that – a more pure sort of lifestyle. The idea that it’s a tough world out there and you need to have your wits about you to survive because the powers-that-be would prefer for you to be in a bad place so you need to counteract that. It made me consider that the paradigm of rock musicians is not only indulgent but kind of old-fashioned. I’d always wanted to be a rock musician and to achieve things, and I felt lucky to achieve these things I’d wanted since I was a kid, but I didn’t want to fall into some sort of cliché. I’d been seen as an archetypal rock guitarist and people liked that about me, but it seemed reductive. I didn’t want my self-image as a person to be like that. I’ve got a lot of respect for the guitar players who came before me but I felt that it was a different time and I wanted to be of my time. When I met these guys, who were around the same age as me, I thought it just sounded like an inspiring way to live and a really good way of not being a clichéd musician.

People may look back at photos or videos or some of the music I was making and wonder where I was going with that. I just didn’t want to live an obvious life and make obvious music. I had just come out of a rock band and I wanted to do everything that wasn’t the obvious path of a guitar player. I wanted the pendulum to swing really far the other way… Now it’s kind of come back.

I remember on the first Healers tour we were opening for a British rock group who will remain nameless. Their tour bus was next to ours. It was rocking with the sounds of some Beatles bootleg — very loud. Maybe there was some pot going down on our bus, but we were listening to some really interesting music. I remember Zak (Starkey – drums) said to me “They’re the ones who are straight.” We’d just been given a load of shit in the dressing room for being non-alcoholic and for all running and stuff. (We were really into psychedelics too, so it’s not like we were AA or anything.) I remember what Zak said made me feel kind of good, kind of progressive… But a lot of my friends stay up drinking and I love hanging out with them. I’ll stay up to 4 or 5 a.m. partying with them. I’m not a judgmental person.

What do you like about yourself?

I assume people are quite nice even if they’re being shitty — that there’s a reason for them being shitty. I like that about myself because it’s useful. It stops you getting too weighed down. It’s handy, though I know it sounds virtuous. I just like people. I know there are really difficult people. Some people enjoy being difficult… they really enjoy it, but snarky is not my default setting.

Do you enjoy being in showbiz — being famous, or would you rather just be a working musician?

I went through a long time in my 30s, in Electronic, when I tried to just be a pop musician while avoiding interviews, photo sessions, touring, and all that. It was interesting, but it didn’t really work. I don’t think it brought out the best in me. Bernard Sumner is an amazing friend. He had to deal with the consequences of me not wanting to tour and put on shows, etc. He’s a very patient person. It seems like a shallow way to answer your question, but I kind of thought to myself “No one wants me to be shy. If you’re going to do what you do, do it with some life and conviction.” I think it was just a phase though, because I’d been lucky enough to get attention for a number of years before that. Sometimes it would be nice to just make really great records. I’m in the studio now in the midst of that process and that artistry, if you like, and I really believe in it. I’m very lucky.

I don’t need the attention and fame to be the person I want to be, but I’m really grateful that people are interested in me and that’s the most important thing. Despite what I’ve said, the scales really go the other way because I’ve never forgotten what it’s like to want to be heard. It doesn’t seem like it was long ago to me — not long ago at all — that feeling of wanting to connect with people through music and playing the guitar. It was so frustrating that to complain about it now would be wrong. I’m really lucky. There are downsides — being judged and people misunderstanding you, but I get a real easy ride. For a really long time I’ve been known more for what I play than what I say.

That’s changing.

It seems to be changing, yes.

LINKS:

Official Johnny Marr on Facebook

VIDEOS:

Photos by Pat Graham

May 29, 2012 @ 16:21:15

Can’t wait for Johnny’s interview! Ok, I can, I’ll wait.

Jul 09, 2012 @ 09:33:15

Really, really fascinating interview

Jul 09, 2012 @ 12:47:05

A beauty I don’t think I’ve ever read an interview where he’s candid for long periods, so that was indeed fascinating.

I don’t think I’ve ever read an interview where he’s candid for long periods, so that was indeed fascinating.

Jul 09, 2012 @ 13:51:48

Can’t wait for part two. Excellent questions and answers.

Jul 10, 2012 @ 04:35:30

how come johnny looked older in the early 2000s

was it due to his clothing or that he gained weight?

great man. would love to meet him someday

Jul 13, 2012 @ 16:13:55

Go on Johnny biggin up the Ardwick Longsight

Linkage: The Stone Roses, Johnny Marr, Modern English’s Robbie Grey, Mission of Burma | slicing up eyeballs // 80s alternative music, college rock, indie

Aug 03, 2012 @ 10:16:56

[...] Johnny Marr, Parts 1-3 Marie Violette shares a sprawling, three-part interview with the former Smiths guitarist in which he discusses his childhood, growing up in Manchester, his career and his ultimate legacy, of which he says: “I want to be remembered for playing guitar pop.” [Ask Me] [...]

Johnny Marr Guitar and Gear Guide | Zing!

Dec 29, 2018 @ 15:05:23

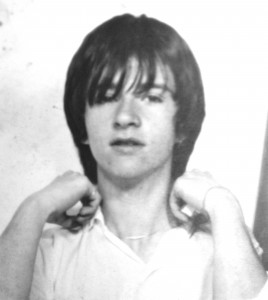

[…] Johnny Marr, 1978, Age 14. Image Source […]